Home › Forums › Guitar Techniques and General Discussions › Applied theory: intervals

- This topic has 5 replies, 4 voices, and was last updated 1 year, 8 months ago by

Jean-Michel G.

Jean-Michel G.

-

AuthorPosts

-

-

February 5, 2024 at 10:34 am #363477

Intervals are one of the pillars supporting the whole music theory construction and it is very important to be able to play them on the guitar.

At the top of the picture below, there are two chromatic scales: one starting from E and the other one starting from C. You can of course start from any note.

The top row indicates the number of semitones between the starting note and any other note. For example, there are 7 semitones between E and B or between C and G when going up. You can also go down; in that case B is down 5 semitones from E and so is G from C.

An interval is just the distance between any two notes; it’s an ascending interval when you go up (e.g. from E up to B), and a descending interval when you go down (e.g. from E down to B).

Every ascending interval has its descending complement; the respective semitones always add up to 12.Intervals have names, as indicated in the table at the bottom left of the diagram.

– the perfect 4th, perfect 5th and perfect octaves have 5, 7 and 12 semitones respectively

– the major 2nd, major 3rd, major 6th and major 7th have 2, 4, 9 and 11 semitones respectively

– the minor 2nd, minor 3rd, minor 6th and minor 7th have 1, 3, 8 and 10 semitones respectively

It is well worth learning this table by heart.Please note: you have to be a little careful when naming an interval. For example, the ascending interval C – G# is an augmented 5th, but C – Ab is a minor 6th. Similarly, C – D# is an augmented 2nd whereas C – Eb is a minor 3rd. This is important in music theory but it won’t concern us much in practice.

Intervals can be larger than one octave; just subtract 12 from whatever number of semitones you have until you get a number between 0 and 12. For example, 23 semitones is the same as 11 semitones, I.e. a major 7th.

On a guitar:

– each time you go from one string to the next you move by 5 semitones (a perfect 4th), EXCEPT when going from the G string to the B string where you move by a major 3rd only

– each time you go from one fret to the next along a string, you move by one semitoneSo for example starting from the note D (A string, 5th fret), you get a major third (4, 16, 28, … semitones):

– by going up four frets

– by going up one string and down one fret (+5 -1 = +4)

– by going up three strings and up one fret (+15 + 1 = +16)

(Always remember the tuning anomaly between the G and B strings!)I encourage you to work out all the other intervals for yourself!

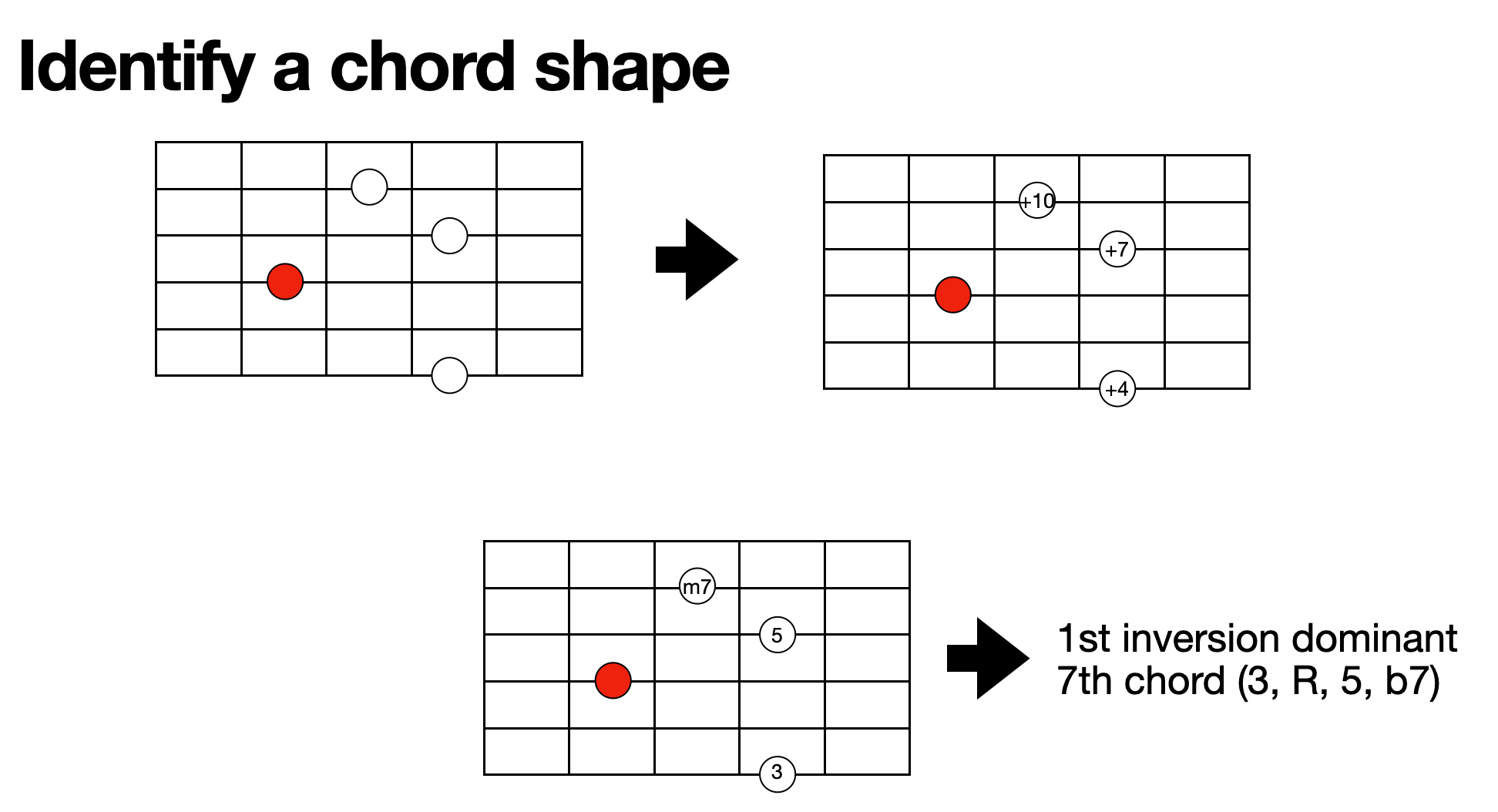

Knowing intervals has all sorts of practical applications. For example, it will let you identify chord shapes. In the diagram below, the red circle indicates the root of the chord:

So:

– on the B string the note is +10 semitones higher, I.e. a minor seventh (b7)

– on the G string the note is +7 semitones higher, I.e. a perfect fifth (5)

– on the low E string the note is 8 semitone lower, or 12 – 8 = 4 semitones higher, I.e. a major third (3)

That chord contains (R, 3, 5, b7) with the 3 in the bass, so it must be a first inversion dominant 7th chord.A very useful thing to do (if you are bored) is learning all possible voicing for the dominant 7th chord; it is then very easy to obtain all the other chords by altering the chord tones of the dominant seventh chord. For example, in the voicing above, if we flatten the 3 it becomes a b3 and the chord is then a first inversion m7 chord. If we flatten the note on the B string we get a first inversion 6 chord. Etc.

I hope you found this useful.

-

February 5, 2024 at 11:47 am #363487

I suspect identifying intervals will be the new YouTube guitar trend. We’ve been through minor pentatonics, mixed pentatonics, CAGED, chord tone soloing and I’ve started to see more and more interval postings. Brian doesn’t really stress intervals but I bet we’ll see some future lessons on the topic.

I’ve always thought identifying intervals was important. Using your favourite roadmap, the octve root pattern, being able to identify any interval within one octave above or below a given root should help improvisation. It’s the smallest, accessible piece of information versus scale shapes, box shapes and 5 or 6 string chord shapes. It should help find chord voicings, scales and arpeggios, also. Of course you have to know your note names to quickly find your roots all over the fret board.

Tom Quayle tunes his guitar in 4ths across all strings such that the interval shapes remain constant without the confusion of the G to B string major 3rd tuning.

John -

February 5, 2024 at 12:04 pm #363489

I suspect identifying intervals will be the new YouTube guitar trend. We’ve been through minor pentatonics, mixed pentatonics, CAGED, chord tone soloing and I’ve started to see more and more interval postings. Brian doesn’t really stress intervals but I bet we’ll see some future lessons on the topic.

In this case, it’s primarily a response to this request.

Tom Quayle tunes his guitar in 4ths across all strings such that the interval shapes remain constant without the confusion of the G to B string major 3rd tuning.

I tried that too, but I gave up very quickly. Most chords become quite unplayable when you do that.

-

February 5, 2024 at 1:02 pm #363498

And that’s what makes it interesting when a guitar player tries to learn to play mandolin: They are tuned in perfect 5ths. Which gives you an interesting result: The strings are tuned the reverse of a guitar. That is, the highest string(s) is E, 2nd string is A, 3rd string is D, and lowest string is G.

Sunjamr Steve

-

February 6, 2024 at 3:18 am #363571

Yes, just like a violin or a cello (in the case of the cello, it’s A-D-G-C from high to low).

I’m not 100% sure, but I would not be surprised to learn that all stringed instruments (except the piano and the harp, of course) are tuned in fifths or in fourths (which is basically the same thing).The violin, viola, cello and double bass are not really meant for chords – double stops at most.

When you only have four strings to manage, chords and scales are equally easy to play. But not with six strings. If the guitar was tuned “all fourths” EADGCF, you would have a very hard time playing most chords on the top strings, particularly higher up the neck. Also, in that tuning, there is an interval of a minor 2nd between the lowest and highest strings and that interval rarely sounds good…

-

-

February 5, 2024 at 1:39 pm #363501

Hi Jean-Michel, Wow very nice. It will take some time for this to sink in but I’m already seeing some things that I didn’t know and need to learn.

Thank you.

Mr. Larry

-

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.