Home › Forums › Music Theory › A quick intro to voice leading

- This topic has 3 replies, 4 voices, and was last updated 5 months, 2 weeks ago by

Mark H.

Mark H.

-

AuthorPosts

-

-

October 12, 2024 at 9:54 am #380224

Voice leading is the art of making chord transitions as smooth as possible.

It is a very broad topic, impossible to cover completely here, but I’ll give you the gist of it so you can start thinking about it for your next jam session…A bit of history

One of the most popular forms of music production in the Baroque period (from 1600 to 1750, roughly) used to be the basso continuo, aka figured bass or thorough bass.

The composer would provide a complete bass line with indications for which chords were expected above it. For example, in the key of C major, a C bass note with the figure 6 would represent an Am/C triad, i.e. a first inversion Am triad. That’s because the interval between the bass note and the top note in this inversion is a 6th (the 3rd is assumed regular and therefore not mentioned).

The rest of the voicing had to be supplied on the fly by the performer, taking into account the additional counterpoint voice leading rules (which were very strict at that time).

Musicians would often compete to provide the best and most elegant solution.

So thorough bass was basically an improvisation game; therefore, we have few practical examples of that art, as actual performances were seldom written down.The art of basso continuo was gradually abandoned, and music became less and less improvised. It survived only in concertos in the form of cadenza’s: the movement would stop on a second inversion tonic chord and the soloist would freely improvise over that harmony for any length of time until the orchestra eventually joins again and concludes with a perfect cadence.

Nowadays it seems that thorough bass is only practiced in music colleges and conservatories in the harmony classes. However, the concept of voice leading is still extremely relevant in contemporary music.

A bit of theory

We will look at voice leading from the sole perspective of rhythm playing (comping), when you want to provide a mellow accompaniment behind a soloist, together with the bass player.Let’s say we have the following chord progression: |C – – – |F – – – |G – – – |C – – – |

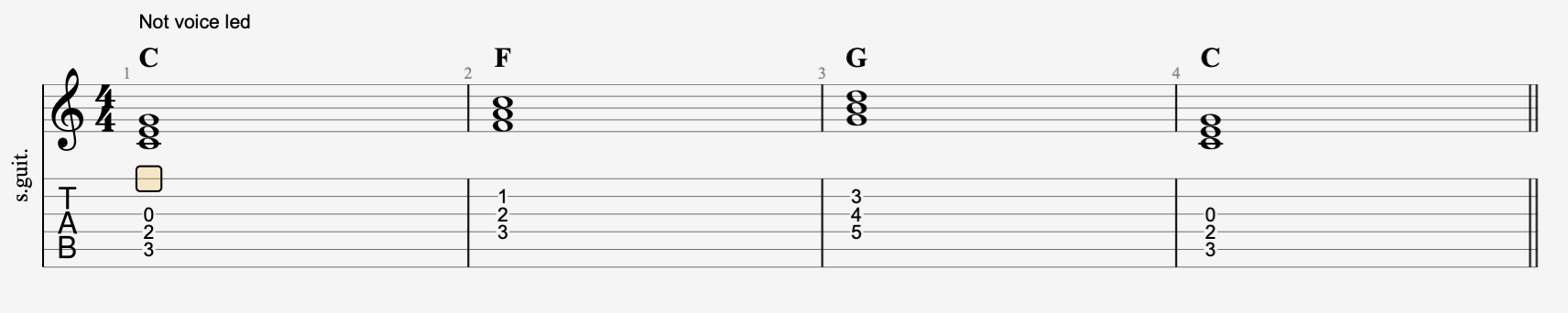

If we play all the chords in root position, we have (C, E, G) -> (F, A, C) -> (G, B, D) -> (C, E, B).

In notation, that would be:If we consider each chord tone as belonging to a specific independent voice, we can distinguish between the top voice (soprano), the middle voice (alto) and the lower voice (tenor). We’ll worry about the bass voice later.

Looking at these voices we notice that in the example the soprano goes g -> c -> d -> g, the alto goes e -> a -> b -> e and the tenor goes c -> f -> g -> c.

In other words, the notes in the voices leap quite a bit, and melodically speaking that’s not very good. Imagine singing any of these voices…In order to improve the situation, we will apply two simple principles:

1. when two chords share one or more tones, keep them in the same voice(s)

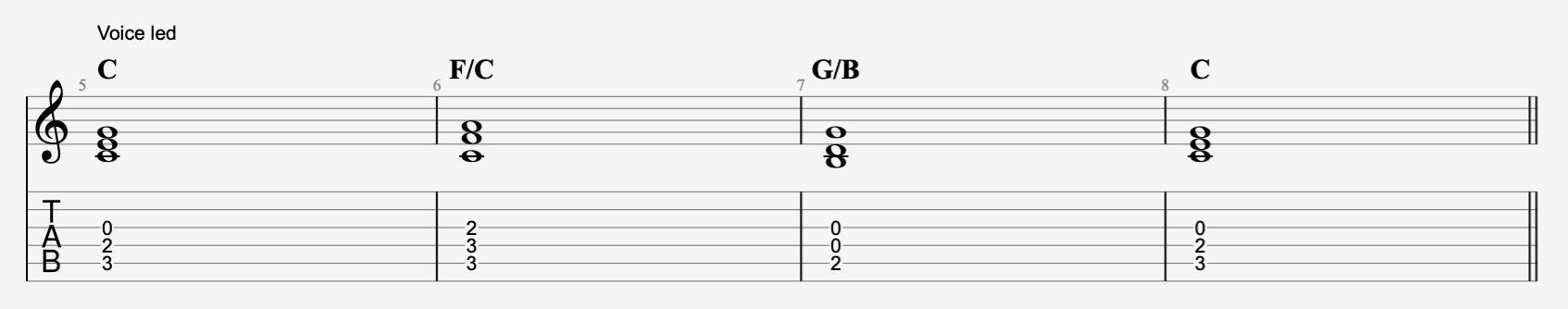

2. within any voice, favor the smallest possible movements from one tone to the next; skips (leaps) should never exceed a major thirdThere are often many solutions; here is one for the progression above:

As you can see, the soprano now goes g -> a -> g -> g, the alto goes e -> f -> d – > e and the tenor goes c -> c -> b -> c; the movements within the voices are much smoother, creating better chord transitions.

Note that the voicings now use inversions, since the root isn’t always the lowest note.

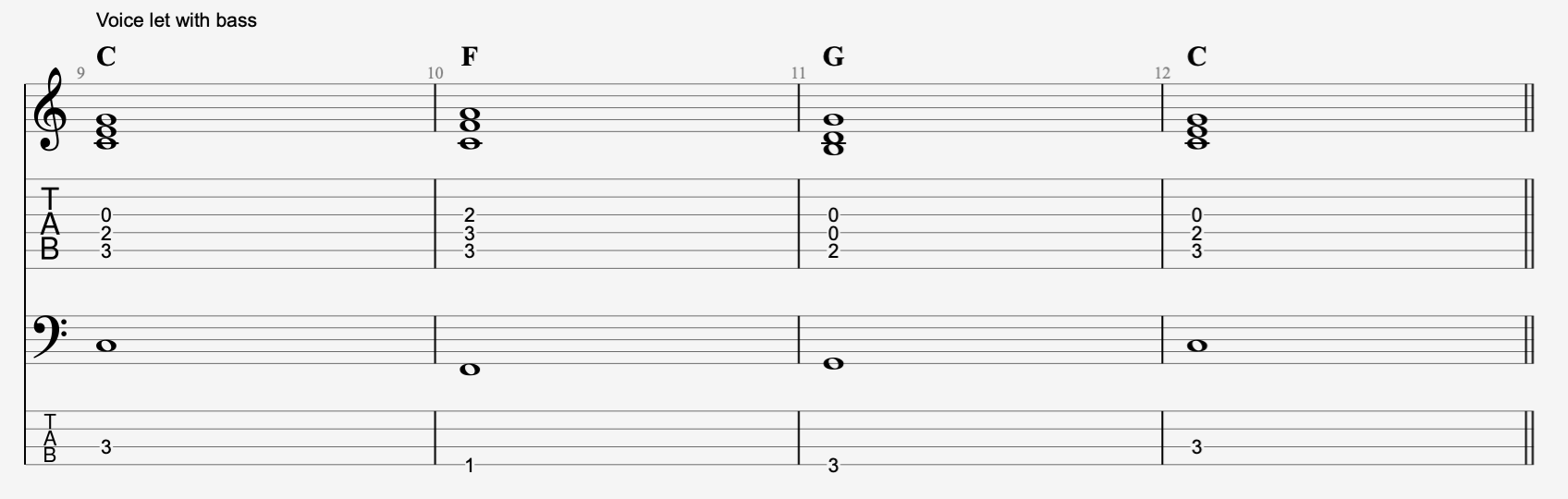

You can of course play these voicings at different places on the fretboard.Finally, let’s add a bass; there are endless possibilities. In the example below, we just play the chord roots and so each full chord (as perceived by a listener) ends up in root position again since the root is effectively the lowest note of the whole voicing.

The movements in the bass are independent and much less constrained than in the other voices; in particular, it’s OK for the bass to jump by 4ths or 5ths and more.

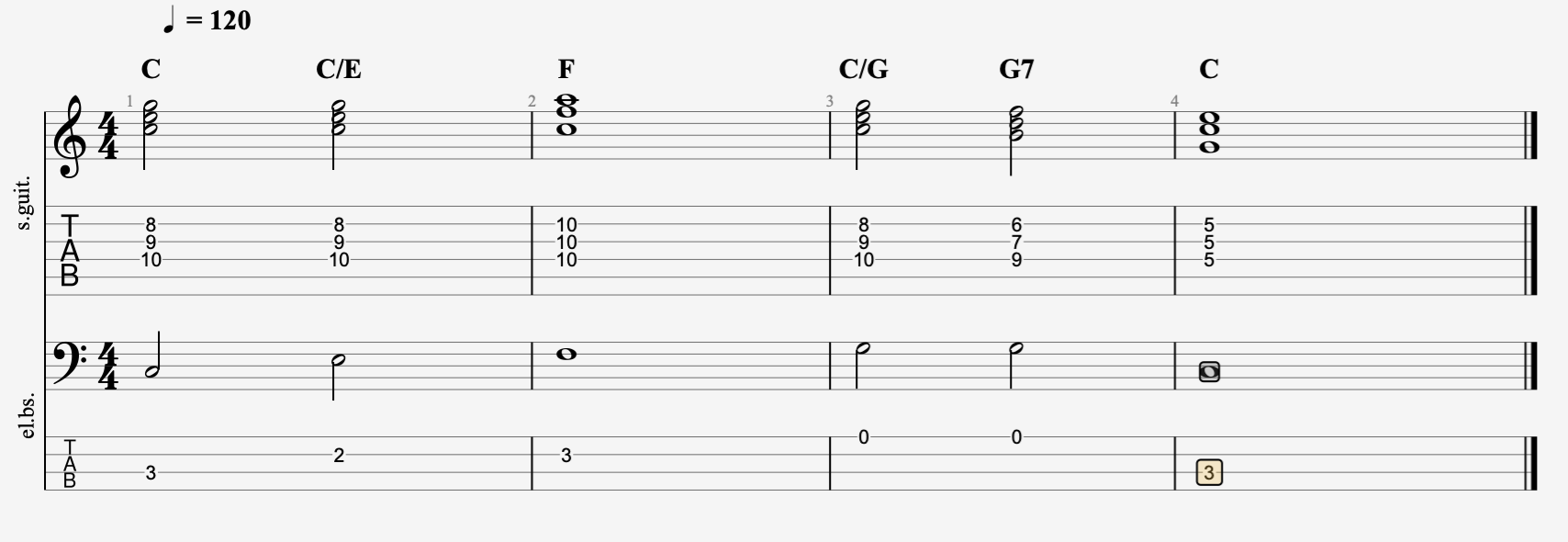

Note that the bass can certainly play other chord tones, effectively creating inversions, in order to tame its melodic line. It can also play much more interesting rhythms, like a real bass player would do. But all that would lead us too far.

Here is a very simple example where the bass line is slightly more active.When chords contain four notes, such as the dominant 7th chords, you can apply the same two principles as above but dropping the fifth of the chord (if that makes life easier). For triads, the “guide tones” are the 3rd and the 5th, but for 4-note chords it’s the 3rd and the 7th.

Conclusion

Life as a guitarist can be perfectly happy without voice leading. Certainly if you play rock or standard blues. But even a basic application of the principles outlined above can make your playing much more sophisticated and will help you better occupy the sound space when playing in a band.As usually: have fun!

-

October 12, 2024 at 7:03 pm #380233

Good stuff. My brain likes to hear voice leading, so sometimes I accidentally do it.

Sunjamr Steve

-

October 18, 2024 at 7:19 pm #380408

I know, right?

-

-

October 16, 2024 at 6:25 am #380328

That was a very interesting read. I’ve always liked the sound of those subtle “voice lead” changes and now I’ve got an understanding of what’s behind it.

That little formula to help choose chords is a piece of gold 👍

-

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.